March 17, 2024

First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

A few weeks back, we used the poem, Fletcher Oak, a head nod to this month’s Earth Teacher, the Acorn. In it, the poet Mary Oliver wrote these lines:

I don’t know if I will ever write another poem.

I don’t know if I am going to live

for a long time yet, or even for awhile

…

But I am going to spend my life wisely.

In the midst of a world on fire; in a life that has too much tragic absurdity, by which I mean, no guarantee of ultimate purpose; in a life where there are few absolute truths, there does not seem to be a map for how to spend a life wisely.

But there just may be a compass…

A compass, not a map.

I recently returned to a book that I read seven years ago – perhaps you read it, too, in 2017, when Braiding Sweetgrass was the talk of the town. Written by Robin Wall Kimmerer, its subtitle is “Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.” Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, a botanist, an academic, and poet. Her storytelling is exquisite.

A compass, not a map.

That’s how Kimmerer describes the difference between indigenous spirituality and Judeo-Christianity. With its ten commandments, she suggests that the Abrahamic religions provide a map, with clear directions for right and wrong. What she was taught, is more like a compass: pointing folks in a direction, but then they have to find their way, each generation anew.

A compass, not a map.

When I heard that, a spark of recognition touched me. Unitarian Universalism also aims, in its essence as non-creedal religion, a religion without dogma, in our honoring the pluralistic nature of Truth and even of wisdom, to be more of a compass, than a map.

Unitarian Universalism with our eight principles, and our seven values, states that we have “a free and responsible search for truth and meaning.” So rather than a map, or even a GPS to tell us exactly where to go, recalculating as we take wrong turns, we have principles and values that aim for an resilient balance between an individual’s free search and the responsibility we all hold within our covenantal community.

This is our work: using the compass of Unitarian Universalism to create a not a map, but a path for a life of integrity, a life in service of a greater good, a life that is whole and holy. A wise life.

What do I mean by wisdom? How do we distinguish between it and garden variety knowledge?

There are books in the Hebrew Bible that have been given the name, “Wisdom Literature:” the Book of Job (my favorite), Proverbs, Ecclesiastes. Affirming that wisdom resides there, our Unitarian Universalism holds that it is not, by far, the only source. This is part of our intrinsic pluralism.

On my free and responsible search to figure out how to spend my life wisely, I found an article in Psychology Today that attempted to quantify the qualities of wisdom. Here is the supposedly data-driven list that Adam Grant generated. Wisdom

- correlates not to age, but to the capacity for reflection

- is connected to the ability to see shades of grey, rather than either/or

- balances self-interest and common good

- reveals a willingness to challenge the status quo

- aims to understand, rather than judge

Wisdom, the author goes on to say, does not guarantee more happiness: people considered by others as wise do not score higher on scales measuring happiness. Wisdom does strengthen one’s sense of purpose in the world.

(Apparently, for a wise person, that would be enough.)

I have wondered about creating my own list of what constitutes wisdom – not to make a map of it but to create(to borrow a phrase from the author E.B. White) the points of my compass. Points of my wisdom compass.

Mary Oliver, in a different poem, In Blackwater Woods, suggests that wisdom comes from the capacity to surrender, poetically rendered thusly:

To live in this worldyou must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold itagainst your bones knowing

“In Blackwater Woods” by Mary Oliver

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

A compass, not a map.

Adding to Surrender, let’s name Humility. This fits with botantist Kimmerer’s ideas. Here are her words:

“In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom.

But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.”

We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn—we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.”

Surrender and Humility: to these, I want to add Generosity.I have long wondered about the role of generosity when it comes to wisdom. Is wisdom some form of knowledge shared generously? Like Spider learned (the hard way) in our Time for All Ages story? Shared without attachment, knowing that it will evolve, that it is a process of ongoing co-creation, often in conversation with others, and will come to serve purposes beyond our current kin or ken?

I ask us to think back to John, from today’s reading by Victoria Safford, with his generous idea of what it means to attend church. Might we consider his generous welcome as wise?

Since John Eric was one of the first people I met when I walked over the threshold of my first Unitarian Universalist congregation, lo these 29 years ago, I would have to say yes, he was. Certainly his efforts seemed to be informed by a balance between self-interest and common good, as mentioned by that social science data.

It seems that wisdom may be a multi-faceted jewel. So far we have three facets: surrender, humility, and generosity. We don’t have time for all the facets, but in the second part of the sermon, I’ll explore three more: interdependence; complexity; and self-differentiation.

Part II

A compass, not a map.

On this journey of figuring out how to spend my life wisely, I have also wondered if wisdom is the capacity to see beyond the apparent, to see the sacred nature of a person or a thing or a place or a moment; to see interconnection and interdependence where others might only see individualism and competition?

I think here of the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh and his teachings that we are here on this earth to awaken from the illusion of our separation. This, too, is an aspect of wisdom. It is also April’s Soul Matters theme, and one of the new UU values: Interdependence, which isn’t so very new, as it is part of the 7th Principle.

When I look at the wise ones whom I have encountered — in person or through stories — I find that they are people who can hold complexity loosely in their hands. They do not fall apart from the strain of contradiction, but are invigorated and inspired: moved to laugh with delight or keen and wail at the tragic absurdity of this life, choosing to go on, to move forward, to not do it alone.

They are the very people who, in a world that wedges and divides, a world that prefers binaries and seeks to calcify false opposites, these people work towards nuance. They – we? – work towards nuance not to avoid taking a side, but because the choice between two sides is often a false one.

Being able to hold contradiction and complexity means that we can condemn the horrific violence being visited upon Gaza, such as the jagged scar of starvation from cruel militaristic human calculation, and also condemn the threat that Hamas poses, making the call for a ceasefire complicated because Hamas offers no reciprocity. Being able to hold complexity means that we can condemn this all without reaching for the culturally-heavy weapon of anti-Semitism when the critique is of a government, not a whole people.

A compass, not a map.

So adding to the first three qualities – surrender, humility, generosity – I have thus far added the capacity to hold complexity, as well as recognition of the interdependent nature of reality. I now want to raise a quality that is required to be a wise clergy person – or leader of any kind – maybe even a wise person. Self-Differentiation: knowing the difference between you and me and being able to set boundaries while staying in relationship.

In my position as your Senior Minister, I was recently confronted with a serious decision. If there was a job description for this position, it might well say, “confront serious decisions on the regular.”For the one that I have in mind just now, I went through an intentional process of discernment. You could say I was on that free and responsible search for truth and meaning.

As I considered as much of the context as I could, it became clear that whatever choice I made, there would be those who thought it was the right decision and those who thought it the wrong one. I’m guessing that I’m not the only one in the room who has been in this sticky situation…

With much reflection, some personal agitation, and with the passage of time, I have come to believe that more than wanting to be right, I want to be wise. Like it or not, that’s the kind of Senior Minister you ended up with.

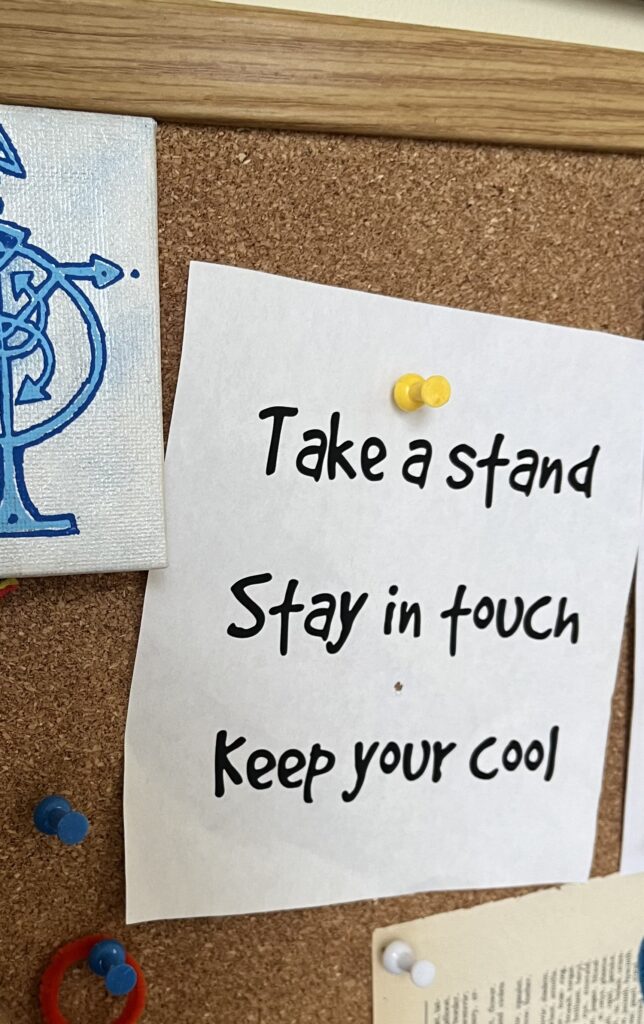

And in this situation, and others I encounter as a parish minister, I find that to be wise, I must practice something taught alot in the era I was attending seminary, that concept I named earlier: Self Differentiation. There’s a three-phrase way to describe what Self-Differentiation is:

Those three phrases are not a map, but they are a compass for me, especially when I am faced with a politically-fraught, emotionally-involved situation. It is a compass for when there is conflict. It is a compass for when someone is focusing their annoyance at me.

Take a Stand. Or, as I like to say, stake a claim. This is when I speak my truth, when I claim where I stand in a particular situation. Like when I set an unpopular boundary.

Stay in Touch. Once I’ve staked my claim, my work is not done. For it is up to me to stay in touch – to stay connected to those who are impacted by my decision, especially those who are upset by it. Those who take a stand but then leave the chaos for others to clean up – that is not wise leadership.

Keep Your Cool. While staking my claim and staying in touch, when emotions might be high and the potential for reaction strong, the wise leader does what they can to keep their cool. This is not an aloof neutrality, but a relational equanimity. I can still have feelings and even show them, but a wise leader attempts to bring what is called “a relatively non-anxious presence.”

My way to spend my ministry ~ and my life ~ wisely.

As we strive to spend our lives wisely, we must come to see that wisdom is a multi-faceted jewel. I have named six facets today:

Surrender

Humility

Generosity

Interdependence

Holding Complexity

Self Differentiation

There are, of course, more facets – ones that I could name, ones that you could name. What about kindness? What about courage? A sense of justice?

What wisdom do we need to tend to the rapidly-depleting soil? To the acidifying oceans?

What wisdom do we need to resist authoritarianism? To bring the damn war against Gaza ~ and all wars, frankly ~ to an end?

What facet of wisdom are you ~ right now ~ cultivating in your life? And if you aren’t sure in this moment, I invite you to spend some time naming at least one facet and choosing it as your companion today and all the days to come.