April 7, 2024

First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles.”

Who wants to be fretting about trifles? Not me. I mean, I think that fretting about trifles, being fretted by trifles, sounds alot like what the Buddhists call “monkey mind” – restless meandering through the land of worry, hopped up on anxiety and alarm and varying degrees of vexation and, well,…fret.

What I’m hoping for, longing for, with this solar eclipse is to mingle starlight with my life. This starlight that, as daylight is robbed of its preeminence for just a moment or two (in the case of our latitude and longitude, for three minutes and fifteen seconds), will emerge in ways that Science can explain but Heart-Mind cannot fully comprehend.

This life, this dash between years carved on a headstone, this dash between the stardust from which I come and to which I will return.

This life, in which I know myself to be in a long chain of generations who have looked up in wonder, in fear, in awe, in terror, in bafflement, in appreciation, in curiosity. Generations upon generations, centuries upon centuries, millennia upon millennia. A long linkage to other humans who have looked up, then all around, to see the colors they thought stable and the reality they solid, both shifting to a platinum tinge.

The woman who said that phrase – mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles – when she was 12 years old, in 1831, observed her first lunar eclipse and helped her father to calculate the timing of the next one. Her father, who, in an era when this was rare, believed that his daughter, a girl, was capable of great things and worthy of formal education. He taught her his love of astronomy. That image you see projected is from a picture book about her life – What Miss Mitchell Saw.

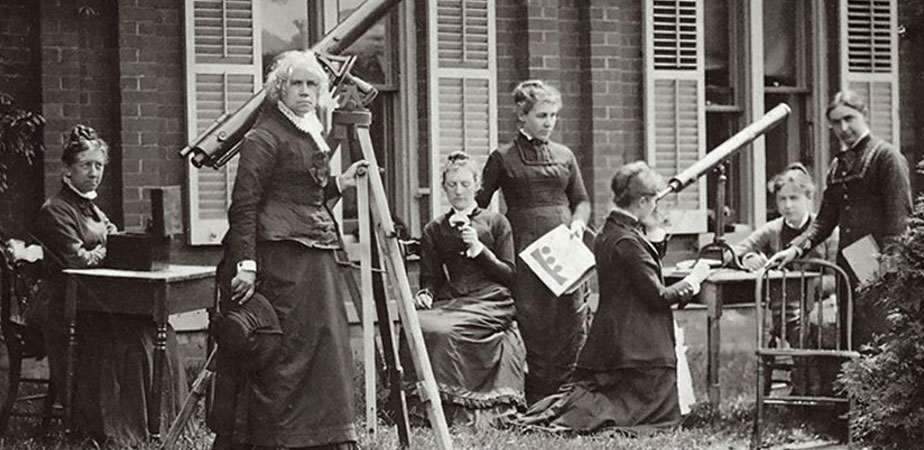

After sixteen unfruitful years of scanning the sky with a telescope, having learned and honed her craft, on October 1, 1847, she was the first person – not first woman, but first person – to see a telescopic comet (invisible to the naked eye). For this, she was awarded a gold medal by the King of Denmark, embossed with these words: “Not in vain do we watch the setting and the rising of the stars”

Her name was Maria (pronounced Ma-rye-ah) Mitchell. When the new Vassar College opened its doors in 1861, dedicated to the higher education of women, Miss Mitchell was its first Professor of Astronomy. She taught there until failing health forced her to retire; a year later she died in 1889.

A decade before her death, in 1879, she traveled with a group of her students to Burlington, not Vermont, where we live, but Iowa, to view the total solar eclipse.

“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles.”

Perhaps her lifelong identity as a scientist fed her skepticism about religion and church doctrine. In 1843, at the age of 25, she was interviewed by two women from within the Quaker community in which she was raised. The young Miss Mitchell shared that her mind was “not settled on religious subjects.” The women concluded that “further labour” to convince Miss Mitchell otherwise, would be “unavailing.”

In her later life, she wrote about her understanding of how god and science complement each other:

“Scientific investigations, pushed on and on, will reveal new ways in which God works, and bring us deeper revelations of the wholly unknown.”

As Unitarian Universalists, it is not clear whether we can rightly claim Maria Mitchell as one of our forebears. Wikipedia tells us one thing (yes). The Unitarian Universalist Dictionary of Biography tells us something different (no).

It is reasonable to acknowledge that she orbited within our faith universe. For part of her early schooling, she attended a school run by the local Unitarian minister. After having parted ways with her Quaker upbringing in her mid-twenties, one source says that for the next two decades, still living on her home island of Nantucket, she attended the local Unitarian church. True to herself, she never became a member, says one source. The website of the Unitarian Universalist congregation on Nantucket calls her a member.

As I was complaining to a colleague about the lack of clarity about any Unitarian provenance for Miss Mitchell, my colleagues thought that we modern UUs recognize in Maria Mitchell a kind of spiritual or religious naturalism, but back in her day, old school Christian Unitarianism probably wasn’t her cup of tea.

Perhaps that is why she enjoyed the company of the folks associated with Transcendentalism, that wild and wonderful exploration of encountering the Holy in Nature – Emerson, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott – not to mention those committed to Abolition – like Frederick Douglass. She did also spend time, while working as the librarian at the Nantucket Atheneum, with more garden-variety Unitarians, like Theodore Parker, Horace Greeley, and William Ellery Channing, too.

Does it matter? Unitarian or not? In the scheme of things, not one iota. For her story speaks to us regardless. The causes dear to her heart – the emancipation of those enslaved, the education of those typically excluded – these speak to us. And the insight she shared with her students, we can benefit from, too:

“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles.”

With gratitude for the loving storytelling that Maria Popova of the online community she leads, The Marginalian, for her dedication to revealing so many beautiful facets of the jewel-like story of this pioneering woman whose life was spent anticipating, chasing, and recording eclipses; finding poetic beauty in the cosmos, and perceiving balance between science and god.

With the upcoming total eclipse of the sun, revealing the starscape in such a rare and rarefied way, may we accept the invitation: do not be fretted by trifles.