First Unitarian Universalist Society Burlington

September 24, 2023

For those of a certain age (older than me, maybe older than you), there may be a recollection of Art Linkletter’s mid-twentieth century television show, and book, which revolved around “Kids Say the Darndest Things.” I want to bring that into this part of the 21st century and say

Recently, I received a text that referred to two “parishioners” (no worries, it was a praiseful text), but instead of showing the word “parishioner,” it said “Two of your prisoners….”

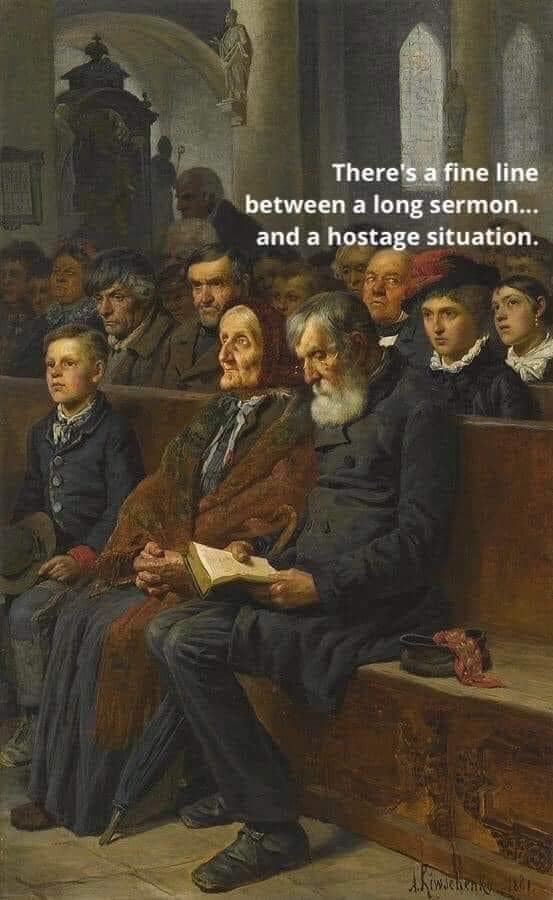

Which made me think of this meme, popular among ministers: along with the image of a painting of a bunch of disaffected 18th century white people sitting in rock-hard pews, it says:

So, you might see why the autocorrect from parishioner made me giggle. So much so, that I made a screenshot, got the consent of the author, then shared it online in a closed online support group for UU ministers, hoping to bring some levity to these people with whom I share this strange and wondrous calling. For some people, it did make them laugh.

And for others, in particular, those whose ministry involves people who are actually imprisoned, it wasn’t so funny. In fact, despite my intention, the impact for them came cross more like a diminishment of their ministries, as if the point of the post were to demean those who are actually prisoners, as if it were to not take seriously that part of some Unitarian Universalist ministries is direct engagement with those who are incarcerated.

One of my colleagues, one whom I do not know personally but whom I respect and admire from afar, called me in on my post. His calling me in was particularly poignant because the power of his ministry around prison abolition is rooted in his own experience of being imprisoned for six months. He questioned why this was so funny, expressing hope that all UU ministries can include attention to prisoner solidarity and needs, noting that we hold culpability in the creation of the US prison system and therefore can and should be responsible for its abolition. (And because consent is so important in our faith, I just want to let you know that he gave permission for me to include this in my sermon.)

Every week ~ probably every day ~ it seems that I have the chance to practice how to respond to this human state of imperfection. This was just a particularly semi-public opportunity. It was a gift from my colleague, his calling me in, a chance to practice what I preach. A chance to recognize harm, even as it was unintended, to practice centering and care for the person who experienced the harm, and to figure out what repair might look like.

This is quite different than how I grew up. I was raised that an apology was the height of one’s response after having made a mistake or caused harm. “I’m sorry” was the start. And usually the end.

Yet, as I have aged (and possibly matured), I have come to find this approach to be lacking. I have found too many apologies to be about making the person who apologizes feel better, rather than the person to whom the apology is being made. Maybe that is why this quote from the late bell hooks resonates so strongly for me:

“I am often struck by the dangerous narcissism fostered by spiritual rhetoric that pays so much attention to individual self-improvement and so little to the practice of love within the context of community.”

bell hooks

Maybe before, but definitely as a parent, I really discovered apology was not enough – not enough when I messed up (which, as a parent, was regularly) and not enough when teaching my kids to be good humans in the world.

It turns out that there are many wise sources for moving us beyond apology. I can’t speak t all of them. I want to give a shout out that the Twelve Step philosophy has a lot to offer in this regard, whether or not addiction is something that has impacted you personally.

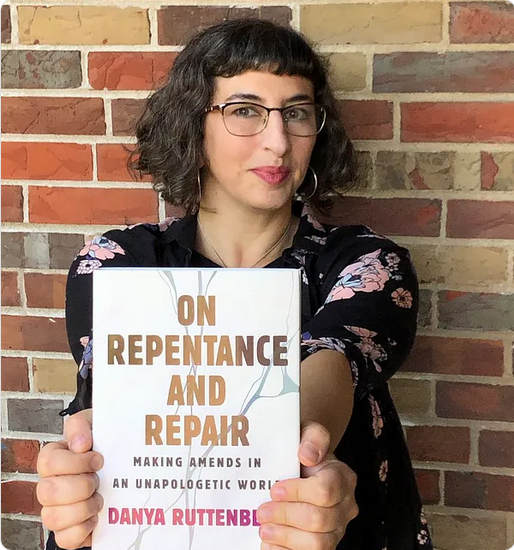

And I want to explore as the heart of this morning’s sermon, what is offered up through a deep Jewish tradition, started by the 12th century philosopher-theologian, Moses Maimonides, offering it to you through the modern lens of the book, On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg.

As our reading today recognizes, these days on the calendar are special within Judaism: starting with the new year, Rosh Hashanah, and ending with Yom Kippur (which begins at sundown tonight and lasts one day), these past ten days are commonly referred to as the Days of Awe. Yom Kippur, as a holiday, is associated with Atonement – finding one’s way back to unity with god (at-one-ment), returning to god, returning to your best self (whether or not god fits into your worldview or not), returning to your best self in relationship to others.

Returning (tshuvah in Hebrew) is a central concept at this time. It’s why we sang our first hymn.

Return again. Return again. Return to the home of your soul.

Return to your best self – not your perfect self – but your best self. And since we aren’t perfect, that will mean making amends for the small and large ways that we have been a part of rupture in our relationships with others, with our community, (with our earth, frankly), and even with ourself. And not just on an individual level, but on a systems level as well.

Because attention to the impact of our behaviors, in particular when they cause harm, is an expression of love: that thing that we claim to have at the center of our Unitarian Universalist understanding of who and what we are. Therefore, accountability to oneself and each other, core to the 8th principle, and is also noted throughout the new values that are under consideration by our faith movement, is an expression of love as well.

You heard these words just a few moments ago, as part of our reading. Let them wash over you again:

Imagine how many deep breaths you would need to take. Imagine how many doors you’d have to knock on, how many phone calls you’d have to make, how many letters, how many lunches and coffees, how many awkward moments with your children and your parents, and with strangers (that cashier to whom you spoke so sharply). Awkward is irrelevant. The task is not about comfort, it is about truth, about wholeness and holiness. Restoration.

On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World, this book by Rabbi Danya, was published by the UUA’s own Beacon Press in 2021 – and just in the last week or two, the paperback version came out. It was chosen as this year’s CommonRead, an annual endeavor to connect Unitarian Universalists across geography, giving us a common object for learning and inspiration, and often a shared point of reference for meaning making

Rabbi Danya wrote this book for everyone, distilling this ancient Jewish wisdom into a secular understanding that is accessible to a wide swath of individuals and communities. Perhaps the most succinct summary of her message is

“any attempt to address harm that does not put the victims of harm and their needs at the center will necessarily come up short.”

In longer form, she writes,

“People hurt one another. Sometimes the harm is unintentional, even born of goodwill and the desire to help. Sometimes it’s the result of ignorance or lack of information. Sometimes it happens because of cowardice. Sometimes it reflects a self-protective impulse—a desire to preserve one’s own self-image or concern about organizational public relations. Sometimes a long process of dehumanization makes atrocities possible. But whatever the cause, people manage to inflict damage in a myriad of ways, from hurt feelings to lost livelihood, the infliction of trauma, the perpetration of hate against a vulnerable demographic, or the loss of life. Sometimes harm can be repaired. Sometimes it can’t. Regardless, in a moral universe, there is work to be done whenever harm is inflicted.”

On Repentance and Repair

Oh, that it weren’t true. That I didn’t have to make amends to my colleague – I mean, I didn’t mean to touch that tender place! Oh, if he would just ignore his own experience and focus on my intention. Sheesh.

Oh, that doesn’t sound too good, does it? It sounds like I am stuck in the “free” part of the “free and responsible search for truth and meaning” of our fourth principle (and our Pluralism value), focused on my freedom to say what I want, no matter its impact, rather than on the “responsible” part, which takes others, and our shared community, into account. That sounds more like ego than love.

Rabbi Danya write the following:

According to Maimonides, a person doesn’t just get to mess up, mumble, “Sorry,” and get on with it. They’re not entitled to forgiveness if they haven’t done the work of repair. (And they’re not necessarily entitled to forgiveness even if they have.) Another human being’s suffering is not magically erased because the person who caused it says that they didn’t mean to do it. This is true in our personal lives, and it’s also true of politicians caught saying racist things, celebrities named as sexual abusers, human resources departments that cover up employee complaints, and governments perpetrating harm against individuals or groups. Fixing damage involves taking specific steps; there’s a process. We can’t ever undo what happened, but we can transform the situation and ourselves.

On Repentance and Repair

Those specific steps – the process of repentance – are as follows:

- Naming and Owning Harm

- Starting to Change

- Restitution and Accepting Consequences

- Apology

- Making Different Choices

Those five steps are easy to name, yet take time to describe as well as to distinguish between. The book does an admirable job of this, giving current day examples from our political and cultural life, as well as some historical ones, grounding the stories within this philosophical framework that is nearly a millennium old. There’s not enough time to go into depth in them, but if there were an adult faith development class (hint, hint), there would be.

- Naming and Owning Harm

- Starting to Change

- Restitution and Accepting Consequences

- Apology

- Making Different Choices

Do you notice that not only are there four more steps than just apologizing, but that apologizing isn’t even first? First is naming and owning the harm. As soon as I read this, it made sense to me. I mean, have you ever had the experience of someone apologizing to you and you aren’t sure they know for what they are apologizing, they are mostly saying the words in order to not have to hear about the harm they have done. Yeah. Or apologizing in hopes of avoiding any consequences for their actions. Yeah, been there too.

And this book is not just insightful about apologies. In reading this book, I got clearer in two ways about forgiveness (which gets way more air time in our culture because of Christian hegemony, but that’s a whole other sermon).

Firstly: no one is required to forgive, even if the person who did harm has gone through a process of repentance and repair with integrity. Repentance is not dependent on the granting of forgiveness.

Secondly: there is a difference between forgiveness and reconciliation. A person can forgive an act of harm without agreeing to reconcile with the person who caused the harm – forgiveness does not require one to return to relationship with that person.

What Rabbi Danya, and Maimonides, are proposing is a process that is more in-depth than a simple apology. It is spiritually-rigorous work. It takes time. It takes attention. In an era of overwhelm and exhaustion, one might wonder whether such a process is worth the time and effort. Rabbi Danya wrote these words, which I take to be a, strong response to that concern

“We can never undo what we have done. We can never go back in time. We write history with our decisions and our actions. But we also write history with our responses to those actions.

We can leave the pain and the damage in our wake, unattended, or we can do the work of acknowledging and fixing, to whatever extent possible, the harm that we have caused.

Repentance—tshuvah— is like the Japanese art of kintsugi, repairing broken pottery with gold. You can never unbreak what you have broken. But with the sincere and deep work of transformation, acts of repair have the potential to make something new.”

On Repentance and Repair

Imagine. Something yearns in us to come round right. Something creaky, rusty, heavy, almost calcified within us tries—in spite of us and of all our fears and self-deceptions—to turn and turn and creak and turn again and come round a little truer. (Again, words from our poignant reading.)

Let us yearn to come ‘round right, and then make amends to bring us closer.

Let us be quick to listen and slow to speak. And then, speak in the spirit of repair.

Let us return to the home of our soul.

Let us move beyond apology.

Let us practice love.

Thank you for every word of this valuable sermon. It is all precious. One suggestion: please change the print to be blacker and easier to read. Just look at the difference between what I’m typing now, and the print in the bulk of the sermon. The quotations are much easier to read than the text itself. It makes a huge difference for older eyes especially. Thanks!

I did some research, made a change – larger font and a bit darker. I think it should make a difference.