Part I

Outside of walking around with a lit chalice all the time, (or wearing one around your neck or as a pin on your lapel, which many of us do) the seven principles of Unitarian Universalism are the easiest way to identify Unitarian Universalism. This can be convenient, particularly to those whose parochial views of religion require a creed, particularly if you are to believe my colleague, the UU minister and Zen priest, James Ford,

But it can also be complicated, because we can start treating the principles not as guides, but as if they are beliefs, when they are much more aspirations, much more about our values and guides for living into them as an association of congregations and as covenanted members with each other.

A little history on our principles: In 1960, as the Unitarians and the Universalists, each a Christian denomination that many considered heretical, joined together and in so doing, developed an original statement of purposes. In the process of crafting it, the debate was so heated it nearly derailed the merger. Over time – about a quarter century, it became clear that the original statement was no longer sufficient. In 1984, a new set of now-called principles was drafted and adopted and much to the amazement of many – since we are not a people who easily agree on much – has been steadily in place since then. You can find them at the front of our hymnbook, or on today’s order of service.

I have heard from many of you that you do not know the principles – you don’t know what each of them is, you can’t name more than one, and you aren’t really sure how they figure into our shared life together. While understandable, since we don’t offer a UU adult education class where this would be covered, it does seem important to ameliorate the situation.

The following is not a adult religious education class, where you might attempt to memorize each of them and expect a quiz at the end. Instead this is a worship experience, where we raise up that which is worthy. Here is this combination of imperfect parables and true stories that you might engage fully: mind, yes, but also spirit and heart and perhaps even body.

So let us begin…

(if not otherwise noted, the story comes from Margaret Silf’s One Hundred Wisdom Stories From Around the World)

1st Principle: The inherent worth and dignity of every person

1st Principle: The inherent worth and dignity of every person

The Stranger’s Gift (retelling of a traditional story)

There was once a village that had fallen on very hard times. The villagers had once been very happy, and their community had been famous for its hospitality and friendliness, and the warmth with which it welcomed strangers.

But something had gone wrong in the village. People had begun to bicker with one another. Quarrels broke out for no apparent reason. Rivalry sprang up where once there had been friendship and trust. The chief of the village was very sad about this. He knew that the people would never be happy like this, but he could do nothing to restore the old times of harmony and peace. Strangers no longer wanted to vist the village. The people stopped caring for it. The village was falling into ruin.

But it happened that one day, a stranger came by. He approached the village like one with a mission, as though he already knew who he would find there. And very soon, he met the village chief. He recognized the sad expression in his eyes, and the two were soon engaged in a serious conversation.

The village chief told the stranger about his feelings of despair, and his fears that soon the village would disintegrate. The stranger told the village chief that eh might know of a way to redeem the lost village and restore it to a real community again.

‘Please tell me the secret,’ the village chief begged the stranger.

‘The secret is very simple,’ the stranger said by way of reply. ‘ The fact is, one of the villagers is actually the Messiah.’

The village chief could hardly believe what he was hearing, yet the stranger had an air of authority about him that was irrefutable.

The stranger left, but the village chief couldn’t resist telling his closest friend what the stranger had told him. Soon the rumor ran through the village like wildfire. ‘One of us is the Messiah! Can you believe – somewhere, hidden among our number, the Messiah is living!’

Now, deep down, the villagers were a godly folk who wanted things to be right in their community. The thought that the Messiah himself might be living among them, incognito, made them see things very differently. Could it be the baker? they wondered. Or the old lady who breeds the chickens and sells the eggs? Perhaps it was old Granny Riley, whom the children were in the habit of taunting because of her scarred old face. The speculation went on and on.

But the funny thing was that after the stranger’s visit, things were never the same again. People began to treat each other with reverence. They lived like peope who had a common purpose, and who were seeking for something very precious together, never quite knowing whether the treasure was actually right in front of them.

Before long, visitors began to come to the village just to be part of the happy, holy atmosphere that prevailed there. The stranger never came back. He didn’t need to.

2nd Principle: Justice, equity and compassion in human relations

Dear Strangers at the Whole Foods, written by Deborah Greene:

(trigger warning: suicide)

Dear Strangers,

I remember you. 10 months ago, when my cell phone rang with news of my father’s suicide, you were walking into Whole Foods, prepared to go about your food shopping, just as I had done only minutes before.

But I had already abandoned my cart full of groceries and I stood in the entryway of the store. My brother was on the other end of the line. He was telling me my father was dead, that he had taken his own life early that morning and through his own sobs, I remember my brother kept saying, “I’m sorry Deborah, I’m so sorry.” I can’t imagine how it must have felt for him to make that call.

And as we hung up the phone, I started to cry and scream as my whole body trembled. This just couldn’t be true. It couldn’t be happening. Only moments before I was filling my cart with groceries, going about my errands on a normal Monday morning. Only moments before my life felt intact. Overwhelmed with emotions, I fell to the floor, my knees buckling under the weight of what I had just learned. And you kind strangers, you were there.

You could have kept on walking, ignoring my cries, but you didn’t. You could have simply stopped and stared at my primal display of pain, but you didn’t. No, instead you surrounded me as I yelled through my sobs, “My father killed himself. He killed himself. He’s dead.” And the question that has plagued me since that moment came to my lips in a scream: “Why?” I must have asked it over and over and over again. I remember in that haze of emotions, one of you asked for my phone and asked who you should call. What was my password? You needed my husband’s name as you searched through my contacts. I remember I could hear your words as you tried to reach my husband for me, leaving an urgent message for him to call me. I recall hearing you discuss among yourselves who would drive me home in my car and who would follow that person to bring them back to the store. You didn’t even know one another, but it didn’t seem to matter. You encountered me, a stranger, in the worst moment of my life and you coalesced around me with common purpose — to help. I remember one of you asking if you could pray for me and for my father. I must have said yes, and now when I recall that Christian prayer being offered up to Jesus for my Jewish father and me, it still both brings tears to my eyes and makes me smile.

In my fog, I told you that I had a friend, Pam, who worked at Whole Foods and one of you went in search of her. Thankfully, she was there that morning and you brought her to me. I remember the relief I felt at seeing her face, familiar and warm. She took me to the back, comforting and caring for me until my husband could get to me. And I even recall as I sat with her, one of you sent back a gift card to Whole Foods; though you didn’t know me, you wanted to offer a little something to let me know that you would be thinking of me and holding me and my family in your thoughts and prayers. That gift card helped to feed my family, when the idea of cooking was so far beyond my emotional reach.

I never saw you after that. But I know this to be true: If it were not for all of you, I might have simply gotten in the car and tried to drive myself home. I wasn’t thinking straight, if I was thinking at all. If it were not for you, I don’t know what I would’ve done in those first raw moments of overwhelming shock, anguish and grief. But I thank God every day I didn’t have to find out. Your kindness, your compassion, your willingness to help a stranger in need have stayed with me until this day. And no matter how many times my mind takes me back to that horrible life altering moment, it is not all darkness. Because you reached out to help, you offered a ray of light in the bleakest moment I’ve ever endured. You may not remember it. You may not remember me. But I will never, ever forget you. And though you may never know it, I give thanks for your presence and humanity each and every day.

3rd Principle: Acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations

The Golden Ball

There was once a little boy who lived in a cottage with his parents. He often used to play out on the hills, and when it began to grow dark, he would go home.

One evening as he was just returning home, the little boy lingered for a while at the door. Far away, across the valley, he saw a beautiful golden ball. He was spellbound. What could it be, and who might own something to beautiful? That day, he made up his mind that he must make the journey to the other side of the valley to find his treasure.

And so it happened that one morning he packed his little rucksack with some sandwiches and an apple, and set off to make the journey to the other side of the valley. It took him all day. He had never been so far before, and it took him a lot longer than he had thought it would. By the time he arrived, it was late afternoon, and he was feeling very tired, and hungry. Eventually, every close to the place he had hoped to find the golden ball, he came upon a little cottage, with smoke curling up out of the chimney, and roses climbing around the doorway. But there was no sign of the golden ball. Shyly, he knocked at the door.

The family from the other side of the valley were very happy to see him – though a little bit surprised, if the truth were told. ‘You must be hungry!’ the mother exclaimed. ‘You are very welcome to eat with us.’

‘Where do you come from,’ the children asked excitedly, and the boy pointed across the valley, to his own little home on the hill, now cloaked in darkness.

‘It’s far too late for you to make the long journey home again tonight,’ said the other mother. ‘We’ll make you up a bed in the corner.’

And so the little boy from across the valley spent the night with his new friends, and as the evening shadow grew longer, they all sat around the kitchen fire, while he told them about the golden ball that he had seen so often from his own home, and asked them where he might find it.

‘We’ve never seen a golden ball like that over here,’ they told him, puzzled. ‘But tomorrow morning, when the sun is rising, we’ll show you our treasure.’

The little boy could hardly wait until the morning. When dawn arrived, the children took him to their doorway, and pointed out their treasure. ‘Look over there,’ they said, pointing straight at his own home on the opposite hillside. ‘Can you see our golden ball?’ And sure enough, there was a little golden ball to be seen, shining back from his own bedroom window. ‘One day, we will go to the other side of the valley, and find our golden ball,’ his new friends told him. The little boy smiled.

4th Principle: A free and responsible search for truth and meaning

What is Life? (a retelling of a Swedish legend)

One lovely summer’s day, around noon, there was a deep stillness over all the forest. The birds had tucked their heads under their wings, and everything was at rest.

One lovely summer’s day, around noon, there was a deep stillness over all the forest. The birds had tucked their heads under their wings, and everything was at rest.

Then a bullfinch popped his head up and asked, ‘What is life?’ Everyone was struck by this profound question.

A rose was just emerging from her bud, and was opening up one shy petal after another, rejoicing in the newly discovered sunlight. ‘Life is Becoming,’ she said.

The butterfly was less philosophical. He flew blithely from one flower to another, snacking everywhere on the delicious nectar. ‘Life is pure pleasure and sunshine,’ he announced.

Down on the ground, an ant was laboring under the weight of a piece of straw ten times his size. He said, ‘Life is nothing but toil and sweat and strain.’

There might have been quite an argument about the meaning of life, had not a fine rain begun to fall, and the rain spoke, ‘Life consists of tears, nothing but tears.’

High above the forest, an eagle swooped, making majestic curves in the sky. ‘Life,’ spoke the eagle, ‘is a constant striving upwards.’

Night fell and soon a man came staggering home from a party. ‘Life,’ he complained, ‘is a constant search for happiness, and a string of disappointments.’

After the long, dark night, at last dawn came, rising pink on the eastern skyline. ‘Just as I, the dawn, am the start of the new day, so life is the beginning of eternity.’

5th Principle: The right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large;

The Weight of a Snowflake Parable

“Tell me the weight of a snowflake,” a sparrow asked a wild dove.

“Nothing more than nothing,” was the answer.

“In that case I must tell a marvelous story,” the sparrow said. “I sat on a branch of a fir tree, close to its trunk, when it began to snow, not heavily, not a giant blizzard, no, just like in a dream, without any violence. Since I didn’t have anything better to do, I counted the snowflakes settling on the twigs and needles of my branch. Their number was exactly 3,741,952. When the next snowflake dropped onto the branch – nothing more than nothing, as you say – the branch broke off.”

Having said that, the sparrow flew away. The dove thought about the story for a while and finally said to herself:

“Perhaps there is only one voice lacking for peace to come in our world.”

6th Principle: The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all;

Based on a true story reported by James N. McCutcheon

A story is told about an incident that happened during the thirties in New York, on one of the coldest days of the year. The world was in the grip of the Great Depression, and all over the city, the poor were close to starvation.

It happened that the judge was sitting on the bench that day, hearing a complaint against a woman who was charged with stealing a loaf of bread. She pleaded that her daughter was sick, and her grandchildren were starving, because their father had abandoned the family. But the shopkeeper, whose loaf had been stolen, refused to drop the charge. He insisted that an example be made of the poor old woman, as a deterrent to others.

It happened that the judge was sitting on the bench that day, hearing a complaint against a woman who was charged with stealing a loaf of bread. She pleaded that her daughter was sick, and her grandchildren were starving, because their father had abandoned the family. But the shopkeeper, whose loaf had been stolen, refused to drop the charge. He insisted that an example be made of the poor old woman, as a deterrent to others.

The judge sighed. He was most reluctant to pass judgment on the woman, yet he had no alternative. ‘I’m sorry,’ he turned to her. ‘But I can’t make any exceptions. The law is the law. I sentence you to a fine of ten dollars, and if you can’t pay I must send you to a jail for ten days.’

The woman was heartbroken, but even as he was passing the sentence, the judge was reaching into his pocket for the money to pay off the ten-dollar fine. He took off his hat, tossed the ten-dollar bill into it, and then addressed the crow: ‘I am also going to impose a fine of fifty cents on every person here present in this courtroom for living in a town where a person has to steal bread to save her grandchildren from starvation. Please collect the fines, Mr. Bailiff, in this hat, and pass them across to the defendant.’

And so the accused went home that day from the court with forty-seven dollars and fifty cents – fifty cents of which was paid by the shame-faced grocery store keeper who had brought the charge against her. And as she left the courtroom, the gather of petty criminals and New York policemen gave the judge a standing ovation.

7th Principle: Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

Soccer Ball Lost in Japan Tsunami Surfaces in Alaska

by Kate Springer, published in TIME magazine in 2012

While roaming the beach on Alaska’s barren, largely uninhabited Middleton Island, radar station technician David Baxter noticed a soccer ball floating off the shore. But it wasn’t until he fished it out that Baxter realized how far the ball had traveled: some 3,000 miles, from its home in Japan, where a disastrous tsunami killed 19,000 people and poured the belongings of thousands of others into the ocean more than a year ago.

According to the Associated Press, Baxter’s Japanese wife, Yumi, was able to make out a name and translate a message inscribed on its surface. And soon enough, Yumi was on the phone with 16-year-old Misaki Murakami from the wave-ravaged Japanese town of Rikuzentakata, the International Business Times reports. “It was a big surprise. I’ve never imagined that my ball has reached Alaska,” Murakami told the Japanese broadcaster NHK Media. “I’ve lost everything in the tsunami so I’m delighted.”

The ball had been a going-away gift to Murakami when he transferred elementary schools in 2005. The Baxters plan to travel to Japan next month and return the soccer ball in person. They may be returning another treasure as well: a few weeks after finding the soccer ball, Baxter came across a volleyball with a similar inscription, belonging to 19-year-old Shiori Sato from Japan’s Iwate area.

Over the past year cleanup crews in the Pacific Northwest have been picking up plenty of debris washed ashore from the tsunami, but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the soccer ball is the first piece that can be returned to its owner.

Part II

In his book, Healing the Heart of Democracy, Parker Palmer names habits of the heart that he pos its are necessary for the health of democracy and our nation as we want to know it. One of these habits of the heart he calls, “Holding Tensions in Life-Giving Ways.”

its are necessary for the health of democracy and our nation as we want to know it. One of these habits of the heart he calls, “Holding Tensions in Life-Giving Ways.”

This is how I feel about our Seven Principles – though we could take each on its own, we are better off – richer, wiser, deeper — when we engage the whole, recognizing each principle as part of a larger, interdependent whole. Just look at numbers one and seven – one tells us that each individual is of utmost importance and the seventh tells us that the collective, the connection, is of utmost importance.

If we were to just hold up the importance of the individual, we would (as many UU congregations have an unfortunate legacy of doing) inadvertently buy into and support the nefarious individualism in our culture that undermines healthy community. If we were to just hold up the primacy of the interdependent web of all existence – well, that one’s harder for me to find the downside of, though I know that an extreme version of community over the individual (which I do not believe is interdependence) means full conformity which leads to perversion of the beauty of natural diversity.

Or as James Ford says,

Within some of the individual principles, a similar tension exists: such as in the forth principle where our search is both free and responsible. Seriously? I mean, which is it? I get to freely search for how I understand meaning or must I do it responsibly, which generally means I must take others into consideration and not be free to always do as I please?

Or in the third, where my spiritual growth includes making room for others spiritual growth – what if their spiritual growth affirms a god I know not to exist? Or vice versa?

Or what happens when efforts to seek justice seem at odds with efforts to be compassionate, which we have seen over and over in liberal reaction to the presidential election and to Trump voters?

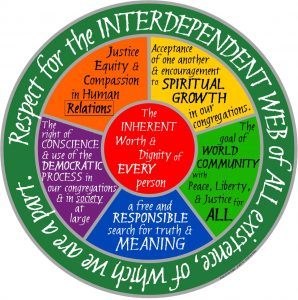

There are many ways to envision the relationship of the seven principles with each other. One and seven as bookends. One and seven as two sides of the same spiritual coin (Ford). As the animated circle on the front of your order of service designed by Ian Riddell and Kimberly Debus. An arched stone doorway, our first principle with its focus on the individual as the left pillar, and our focus on community as the right pillar, with the other five as the heart of the search which holds them in living-giving tension.

Ultimately it does not much matter how you envision them except that you envision them as relevant to your life, providing not a set of beliefs so much as spiritual nourishment and a source of aspiration for living out your life of integrity, for living out our covenanted collective life with one another and the wider world.

May we honor these principles – and each other – and the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.