East Brunswick

September 30, 2018

(This sermon was preceded by the poem, Monet Refuses the Operation.)

Are there Star Wars fans in the house? Can I get a sense with a show of hands: how many of you have seen the most recent Star Wars movie, The Last Jedi?

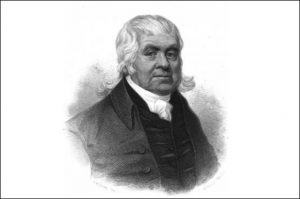

To get everyone on the same page about this, there is the expected hero – a reluctant hero, someone who lost everything, abandoned his past (as well he should, he was a Stormtrooper) but reluctant, sometimes scared, running away. In the movie, his name is Finn. In our own history, he’s John Murray.

To get everyone on the same page about this, there is the expected hero – a reluctant hero, someone who lost everything, abandoned his past (as well he should, he was a Stormtrooper) but reluctant, sometimes scared, running away. In the movie, his name is Finn. In our own history, he’s John Murray.

The unexpected hero – heroine – of The Last Jedi is Rose – a lowly mechanic, fiercely devoted to the resistance and to bringing down the Empire. Rose has a vision and it is one she will not give up on, even when all odds are against it. In our Universalist story, Rose is Thomas Potter.

The unexpected hero – heroine – of The Last Jedi is Rose – a lowly mechanic, fiercely devoted to the resistance and to bringing down the Empire. Rose has a vision and it is one she will not give up on, even when all odds are against it. In our Universalist story, Rose is Thomas Potter.

And in the movie, Rose is the one that says the most important line:

That’s how we’re going to win.

Not fighting what we hate.

Saving what we love.

Remember Finn and Rose. Because now, I’m going to tell you more about John Murray and Thomas Potter, because 248 years ago today, was the birth of Unitarian Universalism’s very own miracle story. But I have to go back a little in history before we can go forward.

Many of the Universalists in New England and here in the Mid-Atlantic emerged out of the ranks of Baptists, unsatisfied with the theology they were given. Through their direct experience of god (I hope you hear there the allusion to the first source of Unitarian Universalism) they came to understand that salvation was universal.

As such, these folks can be considered proto-Universalists and one of the roots that feed what became Universalism, which, I hope it is obvious, became Unitarian Universalism. There are many bright names associated with this heretical sect of Christianity. Some are from England. Some from this country:

de Benneville.

Mayhew.

Chauncey.

Relly.

Hosea Ballou.

Winchester.

Benjamin Rush (one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence).

Olympia Brown – first woman whose ordination was recognized by a denomination.

And the best name, the horseback circuit-riding preacher who visited every state in the union (at the time): Quillen Shinn.

And, of course, John Murray.

I say, of course John Murray, because we just heard a jonty ditty about him – Preach the Gospel of Love, a song that reveals the story of the preacher who lost family and fortune in England, set sail for this continent, got stuck on a sandbar, was found by The Last Jedi’s Rose – I mean, Thomas Potter, and lived out our faith tradition’s very own miracle story – except it actually happened. And right here in New Jersey.

Potter was one of the proto-Universalists – he had come to believe in universal salvation, and it had isolated him, but it did not deter him. He waited ten years after building that chapel for the right preacher – Finn – I mean, Murray – to appear. The right preacher to affirm what his heart already knew: god’s love had to be bigger than anything horrible we mere humans could do, else god not be god. God had to be the very essence of love. God was, indeed, Love.

You don’t actually have to believe in god to see how powerful this understanding of god is.

Turns out that once Murray preached in Good Luck – now Murray Grove – the Universalist watershed was opened. He continued north to New England, eventually rooted himself in Gloucester and Boston, Massachusetts, but traveled some, including back to New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Murray is described both as a zealous preacher, but also not particularly candid. It was still a heresy to preach Universalism – heresy with significant consequences. Universalists – decades and even a century after Murray’s heyday – were considered the source of mayhem in society. If they didn’t believe in hell, what kept them from perpetrating crime? Universalists were sometimes persecuted and accused of crimes they did not commit.

So, Murray was a bit cagey. He used logic, applied it to Scripture, and in his preaching, lead the congregation, step by step, to what to him was a forgone conclusion (god is love, there is no sole Elect who will be saved; instead, all will be), but left it for the listeners to come to that conclusion themselves.

Side note: His preaching was both zealous and logical…and primarily extemporaneous. The Unitarian John and Abigail Adams encountered Murray and found his style of preaching to be… “distasteful” — a quintessential conflict between Unitarians and Universalists at that time that still has echoes to this day in our Association. I’m guessing that was because it was more emotional than the style to which they were accustomed.

Consequences for heresy: pulpits were closed to Murray once his reputation for Universalism got around. Not only that, sometimes there was violence. There is the famous – and true – story of the time Murray was preaching and a stone was thrown through the window, landing near him. Without skipping a beat, Murray walked over to the stone, picked it up, and told the congregation, “This argument” (pointing to the stone in his hand) “is weighty, but it is neither rational nor convincing.” Not unlike today’s fake news: given its propensity, its influence is weighty, but it is not rational and we cannot let it be convincing.

What else do I want you to know about Universalism? Well, as I’ve alluded, having no hell below us was not an easy sell. How do you compel people to be good without fear of eternal damnation? It’s a fair question. One that lives with us today in many forms, including “How is it fair that people can do terrible things and too often seem to flourish?” We see it when we struggle with our First Principle to include people whose actions we find abhorrent.

Nineteenth century Universalists tussled with these very questions. Their answer led to two camps that ultimately created a schism. There were Restorationists – folks who believed that everyone goes to heaven, but depending on how they lived their lives on earth, it might take them awhile to be “restored” to heaven. They didn’t call it purgatory – that’s a Catholic term – but I can’t tell the difference. If you know, please make an appointment and fill me in.

Then there were the Ultra-Universalists – they believed that everyone goes to heaven and immediately, no matter how they conducted themselves in this earthly realm. They had a slogan that has been resurrected on a modern day UU t-shirt. The slogan went “Death & Glory!” meaning that immediately after death came “glory,” (another name for the heavenly hereafter). While it may be hard to see the fairness in this, it is logical within the parameters of Universalism.

And that was one of the things: Universalists welcomed logic. And science. Not fearing either in their understanding of god and the world – another thing that set them apart from some other Christian sects. And like the Unitarians, in the early 20th century, they were initially challenged by the emerging humanist movement. Yet, rather than turn their backs on it, they engaged it, and ultimately, found their balance with it by coming to the believe – and without denying the existence of god — that it was acceptable to no longer wait for divine intervention, but to take god’s work into our human hands.

~~

John Murray had a vision, considered heretical by some, true beyond contemporary dogma, by others. What does the story of John Murray teach us now, all these years later? Is it anything more than just a piece of dead and gone history?

(If it were, I wouldn’t be preaching it today.)

One lesson – a hard one — from the John Murray miracle story is that one person’s vision can be powerful, but it is not enough. A vision, no matter how powerful, how real it is, can be broken and lost in the midst of oppression, trauma and unremitting loss.

Yet here’s the good news, the happier lesson: such a vision, in order to survive, needs to be shared by others, needs safe haven, needs more than just one person to give it shape and life.

This is where Thomas Potter comes in, with his persistent faith, his hope of ten years, enduring mockery from his neighbors, holding fast to a vision he had that it was possible to have a world in which there were no elect or chosen, but that what he would have called god’s embrace was wide enough, more inclusive than what the prevailing culture could imagine at that time.

What if Thomas Potter had not had a vision that caused him to build that chapel? Had not seen beyond what was in front of him, empty land, tangible, yes, but not the reality to come?

What if the vision that John Murray had for himself, sculpted from the rubble of betrayal and violence that led him to flee England, to be done of ministry and preaching, had remained solid, demarcated, untouched by the lens offered by Thomas Potter? What if – and I’m thinking now to our reading of the poem, Monet Refuses the Operation — it had stayed like the way the doctor sees the Houses of Parliament, not like how Monet saw them?

Even bigger, what if their vision of the world, of human relations, and ultimately how they understood god, had stayed stuck in the traditional, the orthodox, the lines clear between heaven and hell? What if they hadn’t visioned that there was no hell below us? That whatever of divine energies there are in the world, they are loving, not damning?

And so we encounter the question – how can we be like John Murray, sure, but how can we also be like Thomas Potter? How can we not necessarily be Finn, the reluctant hero in the Last Jedi– but be Rose, who tells us that in wanting the change the world, in resisting Empire, it is not that we fight what we hate, but that we save what we love.

Save democracy.

Save fairness and kindness in our common life.

Save (or invent) an immigration system that is fair.

Save (or invent for the first time) a criminal justice system that isn’t inherently racist.

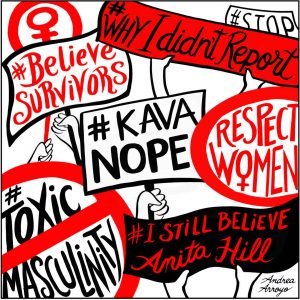

Save a judicial system with judges who don’t harm women in their private hours. Or public ones.

What if we save a world we love in which there is an end of stark divisions in how we see the world, and that beauty and a deep unity are our guides in how we make and remake it – like Monet.

That we save a world we love that believes survivors of sexual assault, that doesn’t produce death threats and hostile, aggressive politicians, or judicial nominees with a barely-hidden propensity for misogyny.

That we save a world we love that not just tolerates, but celebrates, different theological, spiritual, and ethical world views, including – and this is part of both our history and our future legacy – those who do not claim any god as their guiding source, as well as honoring those who do – again, ending needless stark divisions in this realm of human co-existence.

May we, with Unitarian Universalism as the ground below us, covenanted relationship as what holds us together, and good companionship throughout our days, may we be able to see – as the poet’s Monet could – “how heaven pulls the earth into its arms and how infinitely the heart expands to claim this world.”

May we hear ever the call, given to us by our history, re-gifted to us every day we connect with our Unitarian Universalist values and principles, that Love is the guiding force in the world, and can be ours, if we choose it, over and over again – choosing not to fight what we hate, but to save what we love, giving the world not hell, but hope.

May it be so. Amen.